Of the 238,000 students who applied to the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad, one of India’s top schools for MBAs, only 315 were offered a place. That’s one in every 7,500 applicants. Having survived such terrible odds, graduates can rest assured that top global companies will fight to hire them.

Every year, hundreds of leading companies flood Indian business school campuses during recruitment week, meeting every student in person – usually in group sessions - and short-listing some of them for personal interviews. In the end, every student is offered a place.

Compare that to what students in Europe or the US have to go through: as if finishing all those assignments and studying for exams were not enough, they also have to write endless cover letters and tailored CVs to as many companies as possible. If they get lucky, they get to spend days running from one interview to the next, anxiously waiting for that one phone call from their dream employer.

But if the Indian way sounds like a walkover at first, in reality it’s not quite so easy, says Rahul Joseph, first-year MBA student at the IIM Lucknow: “There are people who break down and cry if they haven’t secured a placement during the first day. The tension is immense.”

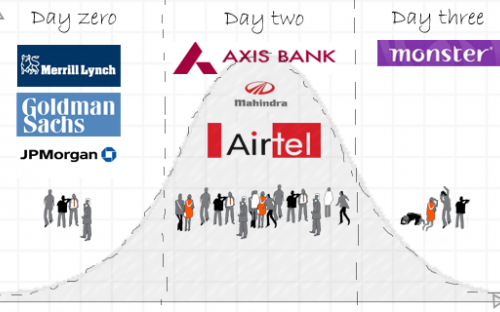

“Day Zero” is the first day of recruitment week during which the most reputable and best-paying companies show up on campuses, looking for the most talented students: “The most prestigious schools, like the IIMs, FMS Delhi or the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad, attract names such as Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan. They offer US dollar salaries of $100.000 and above, with postings in New York, London, Singapore or Hong Kong,” explains Michael D’Souza, who received his MBA from the Indian Institute of Technology in Chennai (Madras) in 2004.

On days two and three, less attractive employers come in, choosing from the students who have not secured a place on day one. The vast majority of Indian business schools place all their students in jobs by the second day: “It’s only the really desperate students at less well-known schools who have to contact a recruitment agency, or put their CV on Monster.com,” adds D’Souza, who is currently working for a leading IT consulting firm in London.

In good years, around three hundred companies come to a campus to assess a batch of three hundred MBAs. “For some people, that means going through three, four, five interviews in one day. They can last until two or three o’clock in the morning,” says Mark Aranha, who graduated from IMT Ghaziabad (near Delhi) in 2008. The whole process, adds Aranha, is tough both for the students and the judging panel.

And it is a huge organizational effort too. Throughout the second MBA year, a representative team of top students and faculty members calls and visits big firms, persuading them to come to their recruitment week. The team collects (and sometimes corrects) the CVs of each student and distributes them to the companies.

According to Aranha, the Indian way of recruiting MBAs makes life easier for the companies, offering them a selection of top students from the best business schools in the country, but not necessarily for the students: “In addition to the competition, it is unfair on those students who did not secure a place in the absolute top schools to start with.”

Those students, he claims, barely have a chance to get a job with one of the best employers, although they may be just as smart and qualified as graduates from the most reputable schools.

Reflecting on the reasons for the difference between the Indian and the US or European way, Rahul Joseph from IIM Lucknow claims that age is a factor: “Traditionally, Indian MBAs enter b-schools straight after their undergraduate degree – they are much younger than US or European students, and also less experienced on the job market.”

In addition, says Joseph, Indian students are used to being “spoon-fed” knowledge throughout their early education, so self-motivation and critical thinking are not things most of them are trained in.

In contrast to Aranha, Joseph believes that recruitment week is an efficient way of placing the best students in the best roles: “Yes, there is a lot of condensed competition over three days. But you also get the chance to appear in front of two or three hundred firms – something that is impossible for EU or US students.” And since b-school is busy and exhausting anyway, “you simply spend much less time looking for jobs.”

RECAPTHA :

11

59

dd

51