The Covid-19 crisis, which first hit the developed world, is now spreading into developing countries. Experts from the United Nations (UN), United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and the World Health Organization (WHO) have stressed deep concern about the long-term impact the pandemic could have on these nations.

Developing countries tend to be poorer, working to become more advanced economically and socially––their infrastructures aren't as established as those you find in Europe and the US. They also rely on primary sector roles––all activities that consist of exploiting natural resources, like agriculture, mining, and forestry––and so they are particularly impacted by disrupted supply chains and lower demand for their goods.

If a poorer country can't sell its resources, then a huge percentage of its national businesses and workforces are going to feel the pinch. Therein lies the problem when a global pandemic hits and their richer trading partners shut their borders.

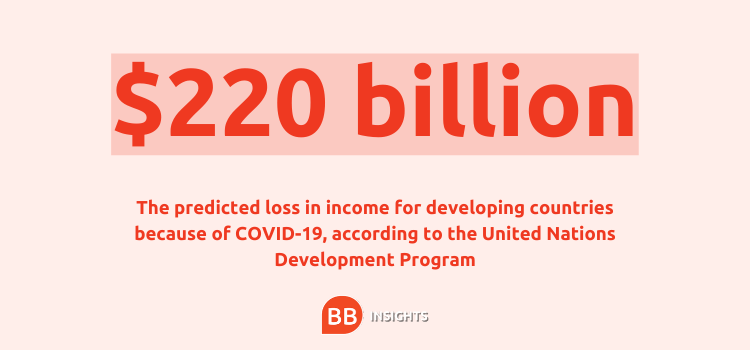

As a result, developing countries could see income losses in excess of $220 billion, according to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

The UNDP are putting plans in place to support them during the pandemic and beyond it, but is it too little too late?

Developing economies | Why will be they be especially impacted?

Developing economies are less diversified. HEC Paris professor of economics and decision science, Tomasz Michalski, says that with increased reliance on fewer industries––largely in manufacturing, resourcing, and tourism––developing countries struggle to continue generating revenue in times of market volatility. For example, with supply chains disrupted by closed borders, manufacturing companies are taking a big hit.

Relations between international economies is something Tomasz focuses on in his teaching, leading courses in Macroeconomics and International Economics in the Grande Ecole and other MSc programs at HEC Paris.

"They have limited room for monetary or fiscal policy intervention,” Tomasz (pictured) explains. If you are wholly reliant on few industries rather than diversified across markets, then there’s less chance you are able to guarantee liquidity––essentially moveable cashflows that can help an economy remain reactive to the wider macroeconomy. If you have cash to hand, then you can move your money more quickly, investing it where it's most needed.

The impact on poorer countries right now

Already, more than 90 developing countries have approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for access to its emergency funding and financial assistance. 24 of the IMF's low-income member countries are benefiting from immediate debt relief so far. But the IMF is calling for the temporary suspension of debt payments to banks for the poorest developing countries.

If we look at Sub-Saharan African governments as an example of how fiscal inflexibility is damaging their economies when faced with closed borders and disrupted supply chains, we’re seeing the impact through depressed commodity revenues (less money for tradeable goods), a collapse in tourism, and lack of foreign investment.

“When you see a drop in demand as we are right now, with tourism for instance, we’re seeing economies being brought to their knees,” independent consultant and lecturer (currently teaching at Stanford Graduate School of Business) Giovanna Prennushi, explains.

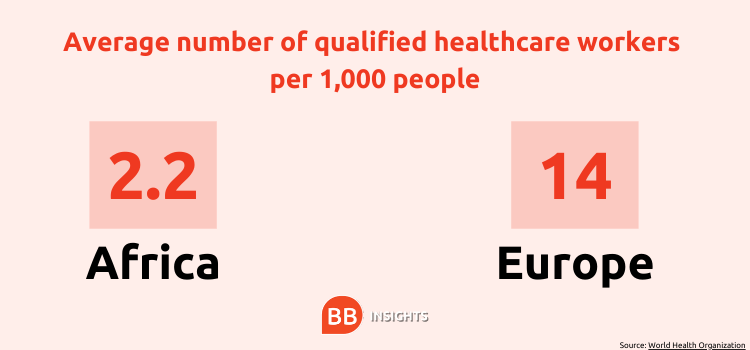

The issue is more than financial. Fighting the impact of coronavirus goes beyond a country's ability to repay debt or keep its economy moving. Healthcare systems in the developing world often lag behind those found in developed nations, both in terms of technology and capacity. This hampers the initial response to dealing with a surge in patients, but also means countries may be less equipped for a second wave of infection.

The stress on healthcare in developing countries

Despite all of this, what’s been surprising is that countries reporting the highest numbers of cases and deaths are wealthier, with developing countries making up just 2% of the global death toll (as of May 2020).

As a former World Bank economist, with over 20 years of experience evaluating and supporting economic development in African and South Asian countries, Giovanna points out that the numbers being reported by developing countries likely don’t reflect the true impact. “The caveat is that the testing done in developing countries is much, much less than what we’ve had in developed countries or in Europe.”

In other words, not every case is identified and reported, due to lack of resources.

This lack of resources and disparity in available healthcare is a big problem for developing countries, Giovanna adds. African countries, on average, have 2.2 qualified healthcare workers per 1,000 people (compared to 14 per 1,000 in Europe). Nigeria is reported to have fewer than 500 ventilators, which are crucial to treating the more serious cases of COVID-19.

“One thing that’s clear is that some countries have better access and funding to top-of-the-line healthcare than others,” Giovanna continues.

Countries like China, who are easing out of lockdown, have begun to offer large in-kind medical donations to less developed countries. Some have labelled this “facemask diplomacy”.

Many countries have turned inward during the crisis, dealing first with the stress within their own healthcare systems before looking to assist other struggling nations. This means developing countries are simply not being offered the same level of support––both financially and through healthcare––than they would if this was a crisis solely impacting the developing world.

“I think the pandemic will continue to widen the gap,” says Giovanna, who has been teaching courses at Stanford that focus on reducing worldwide poverty and addressing economic disparity between developing and developed countries. She fears that the pandemic will undo some of the progress that's been made in recent years. But what will this look like?

Covid-19: The future impact on developing economies

Tomasz predicts that we’re likely to see an increase in emigration from developing countries, as laid-off workers look for jobs elsewhere––most likely in more developed countries. That will have an impact in two ways. It would leave poorer countries with less workers to fill essential jobs and contribute to the economy, and also put pressure on developed countries to support the inflow of new workers.

If developing countries are losing their workforce, then economic recovery will be slower, and the prospect of paying off debt becomes far more overwhelming.

“I expect difficulties in repaying [...] debt in the years to come,” he says. “The situation in many countries may in fact become so dire that they may experience widespread hunger and state failure, with a decade lost to economic growth.”

To put it simply: if developing countries aren’t generating money, they can’t meet the terms of loans provided by developed countries and banks––such as the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank.

Read more on Page 2

What can be done to help developing countries?

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs warns that COVID-19 threatens to undo the progress that has been made since the current Sustainable Development Goals were introduced in 2015. These call for continued work towards ending poverty, as well as promoting sustainability across the world.

Developed countries continue to have a responsibility to developing countries as Covid-19 begins to take root. The World Economic Forum is calling for an increase in official funding assistance, broader debt relief, and the urgent establishment of an international solidarity fund.

But developing countries can also help themselves, Tomasz argues. “What might be needed is a sort of Marshall plan for many developing countries soon, which would create a win-win for both developed and developing countries.

“Such proposals were on the table even before the pandemic, concerning especially African countries in aiding their development and halting immigration to Europe and the U.S. But I am not optimistic.”

One solution Tomasz suggests could be for developed countries and banks to consider writing-off existing debts for developing countries where possible. Developing countries shouldn’t be penalized for defaulting on payments by further restricting their economies through new trade barriers or ‘reshoring’ resource industries, e.g. sourcing textile materials from other countries.

But, as Giovanna (pictured) points out, this can only be achieved if countries––both developed and developing––work together.

“Nobody has a crystal ball,” she admits, “but we’re all realizing the virus is here to stay and need to adapt accordingly. It’s going to change our behaviors for quite some time.”

BB Insights explores the latest research and trends from the business school classroom, drawing on the expertise of world-leading professors to inspire and inform current and future leaders